What MUD Tells Us About Ukraine – Phase Two Starts

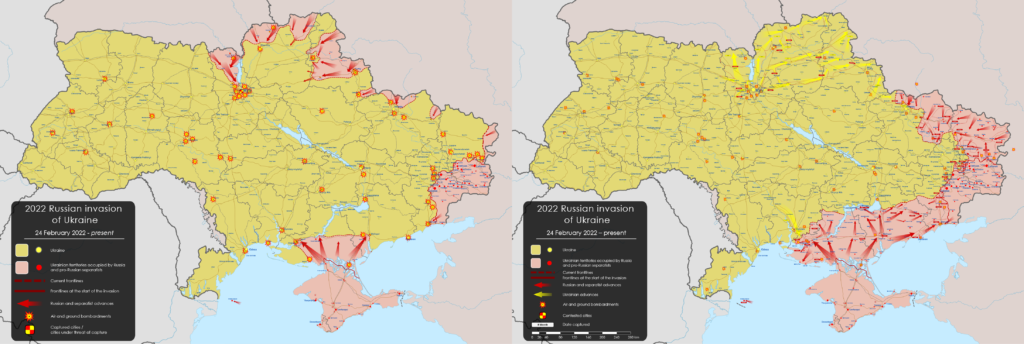

Last week, what the media calls “Phase Two” of the War in Ukraine began. This represents the moment when the Russian offensive switched from a full encirclement of Ukraine into an offensive from the East and represents a complete shift in strategy. Today, we will continue our analysis of the war and, where applicable, draw some correlations to the Modern Units Database to help explain the data behind the actions.

Strategic Shift

In our opening post on the war, we noted three high level strategies for the War in Ukraine. We are now seeing Russia admit that is used and failed Option Three and is moving to Option One. It is still very curious why Russia refuses to adopt Option Two from that analysis, as many analysts suggest this is the best strategy for Russia at this point. Is it because that strategy is exactly what western powers are expecting Russia to do, and therefore they don’t want to do it? Or is there some deeper reason behind it?

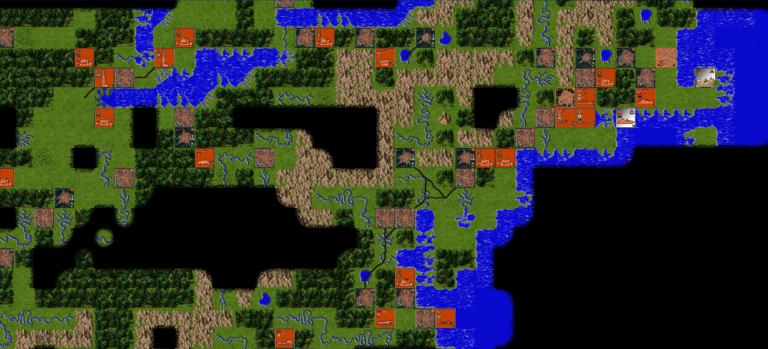

To answer that, the first thing is to understand the option they chose. The main thing that makes Option One a bit more palatable is that the failure of Option Three left a larger front line from which Russia can launch offensives than it did when we first analyzed the opening strategies. There are two important bridgeheads which are now in Russian control and were in Ukrainian control back in February – Kherson and Izium. It’s these two areas which make an assault from the East look like it can achieve Russia’s war goals.

Both are important bridgehead areas on river crossings. The main issue with Option One remains the entrenchments in Donbas, representing a fortified area that will be difficult to assault. If Russia can hold the two bridgeheads, they can sustain a new front that theoretically allows them to surround the Ukrainian troops on the front line and force a retreat or surrender. After two weeks of fighting, it’s clear that they are still attempting this strategy and progress is slow.

Kherson Strategy (Russian POV)

One of the most confusing fronts of the war is Kherson, a small bridgehead which was taken early in the war and remained in Russian hands ever since. The question is why this situation hasn’t changed, despite some recent demonstrations by Ukrainian troops. Let’s look at the strategy behind both sides and see if this sheds any light.

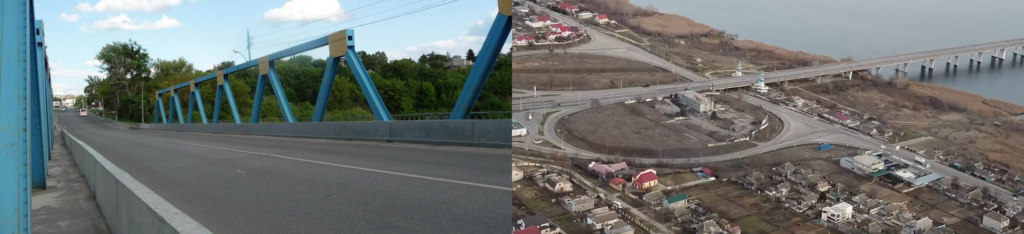

From Russia’s point of view, holding Kherson gives them legitimacy if they decide to perform a referendum and annex the area with Crimea. The Kakhovka Dam is an important strategic area for Crimea in that it supplies water to the isolated peninsula. Therefore, the area was a Day One war goal. However, from the Kakhovka Dam to the Black Sea, the Dneiper only has three major crossing points (Kakhovka Bridge, Prydniprovske Rail Bridge, and M-17 Bridge).

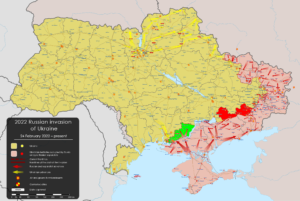

Russia has been pushing west toward Lupareve in what looks like a meaningless direction to attack. However, this is an attempt to secure the mouth of the Bug Liman Estuary that will effectively remove Mykolaiv as a port of operation for Ukraine. It’s part of a larger strategy to starve Ukraine of sea access, which also requires Odesa to be captured.

Stanislav is currently occupied by Russia. Placing anti-ship missile batteries will be placed here after the war ends. To close the estuary, missiles are required to operate over 20km which is doable. The reason for the push towards Oleksandriva, and more importantly Lupareve, is because that distance becomes 5km, thus creating a more secure blockade that is far more lethal.

Kherson Strategy (Ukraine POV)

For Ukraine, numerous news reports indicate constant bombardment of military assets in Kherson. The fortunes on this front could easily be turned against Russia with three carefully placed attacks aimed at destroying their ability to supply across the river. However, it is unlikely Ukraine will take this option because it’s strategically beneficial that Kherson remains an active front.

First, if the three crossing points over the lower Dneiper are destroyed by Ukrainian artillery, Russia will undoubtedly seek revenge on the civilians in Kherson. Moreover, Russia will attempt to construct temporary crossing points so the logistical component of a strike is debatable. The one thing that this certain is a temporary halt to any offensive actions in the area by Russia.

However, the more likely reason Ukraine is not interested in re-taking Kherson quickly is because of the tactical value of leaving this front open. If Russia is required to maintain troop presence here, it means they are not being re-deployed further east. They don’t want Russia to realize that if it simply knocked out the bridges, permanently closed the Kakhovka Dam, they could position defensive systems on the eastern bank and move badly needed heavy weapons to Velyka Novosilka.

As a result, Ukraine is not likely to push very hard on this front unless Russia starts momentum towards central Ukraine. Moreover, Ukraine knows that Russia isn’t likely to allow the western bank to be assaulted. Even if Kherson and Kozatske (western bank near Kakhovka) are somehow re-taken, the Russians will destroy, mine, and defend any potential crossing points. Re-capturing all of Kherson Oblast is out of reach for Ukraine for the time being, so there is little to gain from re-taking the area.

The Russian Airforce

Numerous reports have indicated that the Russian Air Force seems to be missing in Ukraine. While there have been a few sightings, most of the air combat is taking place at low altitudes and with cheaper rotary aircraft. The Ukrainian military is quick to point out that its ground-based AA systems have been denying air space to Russia. While true, this isn’t the full reason that Russia isn’t committing anything. Believe it or not, it’s all related to Afghanistan.

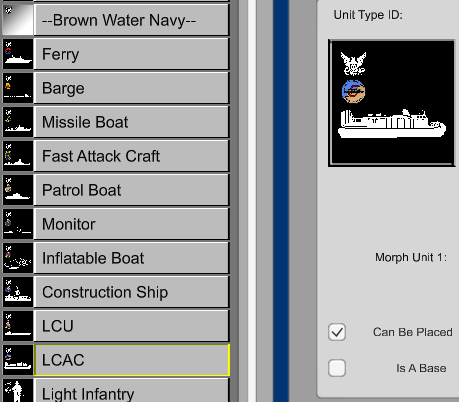

That’s because Russia’s true enemy isn’t Ukraine, it’s NATO. The wars of the past 30 years have all shown that air superiority is the key to obtaining offensive positions in a military zone. Afghanistan fell very quickly because of this. Modern military aircraft are expensive to build, meaning their losses can be irreparable. The Modern Units Database puts the loss of one “somewhat modern” air frame at 170 points, which is the same as losing up to 820 ground troops per plane shot down. Therefore, losing a helicopter with troops, amounting to 70 points per loss, is easier to accept, and thus why the air war is limited to low flying aircraft only.

If we look purely at the numbers, Russia has one third the personnel of NATO, and is at a 5 to 1 disadvantage in serviceable air frames. However, this ratio is still enough to deter direct air strikes against Russia. Much like a fleet in being in World War II, an air force in being means NATO cannot launch air strikes with impunity as they did in Afghanistan where there was no threat to air losses. While this ratio will mean they will be permanently on the defensive, it delays NATO’s ability to dominate the skies on day one.

This is the reason for the limited interest in NATO sending its fleet of aircraft to Ukraine as it will diminish this ratio in Russia’s favor. Moreover, they are hoping that Russia will eventually commit its air forces, allowing Ukraine’s cheap ground-based systems to cause significant damage. Moreover, a lesson right out of the USAF playbook in Afghanistan, forcing Russia to commit air assets in Ukraine will lock them up permanently to this battlefront in the same way that the United States suspected Afghanistan would do to US assets if a global war erupted elsewhere.

Lastly, we haven’t even talked about the third player in this which is China. As the world’s next largest air force, and a potent military opponent, neither NATO nor Russia really wants to contend with another potential aggressor. The United States would prefer to keep its air force prepared for a war against China, while Russia could be directly threatened by China if they lose parity in numbers. As a result, every nation has a reason not to commit air forces to the region.

Scandinavia Threatens Russia

One thing wargaming teaches us is to determine how important our war goals really are. Games make this easier to decide by making unobtained war goals painful. In real-life, this artificial pain doesn’t exist. As we saw with the switch in war goals this month, Russia just needs to justify a win not necessarily achieve one.

The reason games make unobtained war goals painful is because it teaches us to temper our actions until we are sure we can win. After all, if you end up in a worse position than when you started, you probably shouldn’t have done anything to begin with. Forget about the situation on the ground for a minute and realize that Ukraine is no longer the real threat to Russia. It’s Finland and Sweden, since it looks like they will join NATO. If Russia thought it was having a hard time beating Ukraine, then a war closer to home against an even stronger NATO backed ally will be even harder.

These two countries are not weak. They have their own homegrown and renowned military industry. Moreover, they have their own air force, including their own domestic air industry. Pair this with the fact that they are roughly 150km from St. Petersburg and you have a very serious threat Russia. In fact, I would argue that Finland is a far greater threat to Russia than anything Ukraine represented. To make matters worse, this opens an entire front that is only 130km from the naval bases in the north, leaving Russia in a position where it will have to pick what it wants to protect and what it wants to sacrifice.

Russia needs to find a way to end the War in Ukraine quickly so it can start preparing for threats closer to its industrial and financial centers. The introduction of Finland to the war puts additional necessity that it must protect Crimea at all costs. Odesa might be out of reach following the Moskva sinking, but if it plans to continue the occupation of Transnistria it has to at least try. If they do, and they lose, Russia can still bank on the fact that Ukraine is unlikely to take the land war into Russia as it risks losing the support it gained from the west.

Hello Thunderous Cadence! It’s been a while since you posted on this subject, but it looks like the bridgehead option you mentioned is really happening. You should consider posting an update on where you think things will go from here. Thanks!

Hello Mar. Let me look into it as it’s been a while. Is there a specific thing you want me to review?

Keep in mind, this analysis is a point in time review of the situation and may not reflect what really happens.

I’m referring to the Antonivsky road bridge which I think was hit last month. It’s the one you are referring to in this post.