Analyzing the Day One Strategy of the Russian Offensive (2022)

It’s not often that a two modern armies enter conventional warfare in the modern age. Ever since the Proxy Wars of the Cold War became the norm for modern warfare, one-sided asymmetrical warfare was common. However, the War in Ukraine has given us the opportunity to review the accuracy of all the statistical projections that World of Nations, and to some degree the Modern Units Database, have long since suggested if two modern and well-equipped armies fought against each other. This post is the start of a series that will be analyzing the situation and validating if the assumptions made by WoN and MUD were correct.

This post represents a new category that I am adding to the journal. I’ve been wanting to expand this to look beyond just gaming, and it made sense that this be the first topic to cover since I got flooded with questions on how the war affected the MUD statistics and if I needed to make changes, and even asked if I would be re-opening the Worlds of Nations Ukraine Conflict scenario for people to review/play. As a result, I felt this was the time to start this new approach to the website.

Worlds of Nations Probability Engine vs. Real War

Before we get started, if you are reading this in the hope that I will attempt to invoke an emotional response to the war, think again. there are plenty of posts, news headlines and propaganda out there that will do that for you. While propaganda and media positions may be referenced in what I do here, they are for explanation/citing purposes only do not represent the position of the WoN team. You are welcome to debate that with me privately if that is your wish.

WoN has long been a statistical probability engine that was converted into a wargame political intrigue simulator. One of its strengths is on combat logistics (an often overlooked aspect of warfare) and uses numbers to predict the likelihood of events. This means that it focuses on aspects that are measurable or predictable to determine the outcome of conflicts. It’s also worth noting that, while some military analysts do this for a living, the groups that we interact with are not, and should not, be considered a reliable source of official information. Moreover, the field of logistics is a niche understanding and thus you are likely to find conflicting opinions when compared to spheres that conduct their own analysis from a different perspective such as weapon potency and the impact of propaganda.

Russia’s Invasion Strategy

With that said, let’s use this first discussion of the War in Ukraine to give some background. Note that I am posting this at the end of the second week of the war. If things change in the future and you are returning to this page for reference, the information may no longer be accurate.

Prior to the invasion, the threat from Russia was well known and expected. In the latter half of 2021, when the world’s eyes were on Afghanistan, those focusing on Ukraine noticed an invasion strategy emerging. Based on troop dispositions and rhetoric from Moscow, there were three general approaches that were expected when Russia ultimately attacked. Russia had the initiative on determining which strategy to implement, as Ukraine could not take any preemptive action.

From Ukraine’s perspective, they knew the attack was coming. What they didn’t know was Russia was expecting the 2014 Ukrainian military to defend the country, not the well trained and equipped military force that was entrenching around the country. Ukraine further believed that it was going to quickly lose its centralized command and control and needed flexibility to operate independently in defensive positions throughout the country. This meant using lighter weapons than their adversaries. As a result, heavy equipment is placed in heavily fortified fronts, especially in the east where it expected the primary attack to emerge, and the rest would rely on hit and run tactics.

Option 1: Invade from the East

The attack would originate from already occupied territories in Donbas, Luhansk, and Crimea. This strategy would be a full-bore frontal assault against prepared Ukrainian positions. The implementation of this strategy would be a textbook case of the Deep Operation Doctrine that was a staple of Soviet/Russian military doctrine since World War II. In fact, it would be so textbook, that it would have been very clear if the Russians were winning based on how well it was performing according to the progress being made each day.

There are several reasons why this was a good option. Chief among them is legitimacy. The Russians, much like they did in 2014, could claim the equipment is being used by resistance forces. NATO and EU response would be limited, and would have caused longer debates around how far to take sanctions against Russia. Moreover, withdrawing from the conflict if things weren’t going well would have been easier. Russia could have kept this as a proxy war.

The cons to this, however, are significant. The Ukrainian military was well prepared for conflict on this front. The first days of the war would have been intense and bloody. The resistance would be fierce and casualties would be in the thousands per day. If Ukraine was willing to just capitulate, this would have put Russia in a worse negotiating position than other strategies because it wouldn’t gain enough leverage on Ukraine due to focusing only on one front. If Russia took this option, it would have likely resulted in terms from Ukraine that included independence for the breakaway regions, but not a buffer state along the Russian border or cessation of Ukrainian ports on the Black Sea. These were the objectives that were strategic for Russia that couldn’t be obtained with Option One as any assault would have likely stalled out before it reached the Dneiper River.

Option 2: Full Eastern Frontal Assault

Before the war started, most analysts predicted this as the most likely strategy for Russia. It made the most sense and had the highest probability of success. In this scenario, Russia uses its superiority in armor to overrun the defenders along the entire eastern front, including the northeast around Sumy and Kharkiv. Ukraine was likely to concentrate its forces in urban areas and civilian centers, allowing Russia to control the countryside. Russia’s Deep Operation strategy was suited perfectly for this type of open field warfare. Moreover, the secret objective of Russia could have been secured using this method. It was likely they could reach the Dneiper River within a three week window if they avoided urban warfare, which would have allowed them to encircle the fortified defenders in Donbas and Luhansk.

To western analysts, the benefits on this strategy were many. On paper, Russia maintained superiority in armor capability over Ukraine. ATGM’s are a great weapon, but infantry are slow and vulnerable in the open, meaning they have to be positioned in the right place at the right time to be effective. If you simply go around them, the weapons are useless. Moreover, Ukraine’s lack of counter-offensive capability meant that once territory was fully secured, it was likely to remain that way. Thus, Russia’s ultimate goal of creating an East Ukraine that goes from the Dneiper to the Russian border was a real possibility.

The miss by western analysts was the assumption that Russia would operate mobile warfare the way the United States did in Iraq and Afghanistan. In those wars, US forces were able to avoid decisive defeats in battles where they did not have a clear upper hand. The problem with expecting this doctrine to work in Ukraine is a lack of understanding on Russia’s logistical network to support that type of warfare, or the Ukrainian ability to disrupt that network. Moreover, the lack of occupation of major city centers put them in a weaker negotiating position, which was Russia’s ultimate goal. The US, on the other hand, did not intend to negotiate with the remnants of an Iraqi or Afghan government when they employed this tactic and used local forces to conduct more risky missions.

Option 3: Full Encirclement

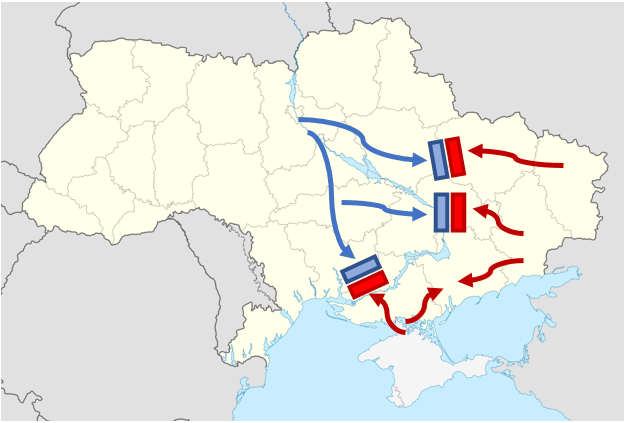

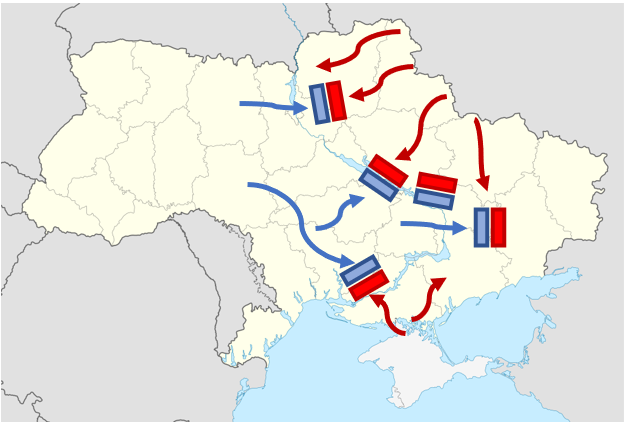

This is ultimately the strategy Russia chose to adopt. The idea was to attack all four sides, causing Ukraine to stretch out it’s military assets, weakening it’s positions across the board, and allowing Russia to focus on its true objectives while Ukraine had to defend on all fronts. Lightning strikes into key areas securing forward positions would allow Russia quick access to strategic targets in case it encountered resistance. It would be the shining example of how Russia’s version of blitzkrieg was meant to operate, bypassing defended positions and attacking from the rear on all fronts.

Take hindsight out of the picture and you can see this made perfect sense at the time. Russia’s recent experience with military invasions showed that a defender, faced against a technologically superior enemy, was likely to capitulate with little resistance. Even the 2014 Ukrainian Conflict supported this when the Ukrainian military offered little resistance in Crimea and Donbas. Moreover, the recent events in Afghanistan showed the world that even a prepared military would likely capitulate instead of fighting an invader. It was entirely likely that, if Russia entered Kyiv, NATO was likely to extract officials and establish a government in exile instead of fighting off the invaders. A quick march into Kyiv was therefore the fastest way to end the conflict with Russia obtaining all of its war goals.

The problems with this were many. The main one is the length of the battle front. By putting troops on three sides (Crimea, Kharkiv, and Kyiv), it couldn’t even support the western position in Transnistria. The Russian positions were just as stretched as the Ukrainians who had the advantage of being on the defensive. As a result, Russia would spend the first two weeks attempting to organize and deploy its forces along all fronts. Then, it had to consolidate its forces around completing one single objective instead of advancing on all fronts. This is coupled with the fact that initial advancements were allowed to pass through the front lines, allowing softer targets behind the vanguard to be assaulted. In other words, Russia had the will but not the way to make this strategy work in the end.

It’s a bit ironic that most western analysts saw this deficiency and as a result never though Russia would act on it. Unfortunately, this is the route they took and inevitably led to some of the most visible challenges seen throughout the conflict.